It’s strange to reflect that listening to all the records below has given me a pleasant feeling of nostalgia. Not that any of this music is old-fashioned as such, although it could be true that the musicians are rediscovering a prior generation and assimilating the lessons of that time into modern practice: it goes around in cycles, never quite the same each time. I think it’s that there’s a kind of exuberance found in a lot of this stuff that had been tamped down in previous decades, with freewheeling exploration that’s unconcerned with accidentally revisiting what has been done before, caught up in the feeling of doing something new. This taps into reminiscences of youth, when the inner creative world suggested boundless potential.

Ishmael Ali / Aaron Quinn: Sometimes Cats Have Puppies [Tripticks Tapes]. A lot of free improv is like jam bands: good ones can be fun when heard live but don’t feel rewarding when heard on record. This duo plays cello and guitar, an unusual combination which doesn’t seem too promising but redeems itself because it never really sounds like what it is. Not that they attempt to disguise themselves; Ali goes for depths of timbre on his cello and Quinn sticks mostly to pointillistic effects with minimal noodling. They are also beset by samplers to disrupt their comfort zone and use digital synthesis to noisy and occasionally startling effect. This is all recorded from a live date so the spontaneity is on-point and the inventiveness of their sounds makes up for the lack of form.

Ishmael Ali / Aaron Quinn: Sometimes Cats Have Puppies [Tripticks Tapes]. A lot of free improv is like jam bands: good ones can be fun when heard live but don’t feel rewarding when heard on record. This duo plays cello and guitar, an unusual combination which doesn’t seem too promising but redeems itself because it never really sounds like what it is. Not that they attempt to disguise themselves; Ali goes for depths of timbre on his cello and Quinn sticks mostly to pointillistic effects with minimal noodling. They are also beset by samplers to disrupt their comfort zone and use digital synthesis to noisy and occasionally startling effect. This is all recorded from a live date so the spontaneity is on-point and the inventiveness of their sounds makes up for the lack of form.

Javier Areal Vélez: Trifasica [Strlac]. A guitarist makes the move from their tired old axe to pure laptoppery. This is all Max/MSP and Ableton Live, apparently, coded with a partly-automated sequencer that adds a hefty element of generative composition to each of the brief essays. You can listen out for signs of guitarist influence, which you’ll mainly hear in the percussive stuttering (no, not like Oval). The sounds get chopped into fragments of irregular rhythm, occasionally letting something more than a beat seep through and wash over the barrage of loops. It’s a promising start; the blunt loops could get wearying after a while but keeping it down to five tracks in eleven minutes should be OK.

Javier Areal Vélez: Trifasica [Strlac]. A guitarist makes the move from their tired old axe to pure laptoppery. This is all Max/MSP and Ableton Live, apparently, coded with a partly-automated sequencer that adds a hefty element of generative composition to each of the brief essays. You can listen out for signs of guitarist influence, which you’ll mainly hear in the percussive stuttering (no, not like Oval). The sounds get chopped into fragments of irregular rhythm, occasionally letting something more than a beat seep through and wash over the barrage of loops. It’s a promising start; the blunt loops could get wearying after a while but keeping it down to five tracks in eleven minutes should be OK.

Gaudenz Badrutt: Palace [Bruit]. This has started to grow on me, thanks to the depths of its conceptual premise and construction. A two-movement composition of collaged sounds and music compiled across several years, Palace combines music (Badrutt playing Ives, Cortot playing Chopin), electronic noise, personal recordings including Badrutt’s young daughter) with heavy processing to create what aspires to be “symphonic density”. Like an Alvin Curran collage but with an emphasis on mood and overall effect over detail, Palace hits first as a work of textural ambience, one which never gets cluttered or opaque, then starts to reveal its fleeting moments little by little.

Gaudenz Badrutt: Palace [Bruit]. This has started to grow on me, thanks to the depths of its conceptual premise and construction. A two-movement composition of collaged sounds and music compiled across several years, Palace combines music (Badrutt playing Ives, Cortot playing Chopin), electronic noise, personal recordings including Badrutt’s young daughter) with heavy processing to create what aspires to be “symphonic density”. Like an Alvin Curran collage but with an emphasis on mood and overall effect over detail, Palace hits first as a work of textural ambience, one which never gets cluttered or opaque, then starts to reveal its fleeting moments little by little.

Ilia Belorukov & Lauri Hyvärinen: Fix it if it ain’t Broken [Nunc]. Hyvärinen, recently heard on the cutting set of electric guitar duos with Jukka Kääriäinen Pulled Apart by Horses, pairs up with Belorukov’s modular synth. The shredding is more literal than usual, with Hyvärinen making extensive use of sampling pedals to feed his guitar into various mangling digital effects while Belorukov produces slabs of quasi-analogue noise. At times the guitar seems to act as a foil to the synth, or the two trade different flavours of electronic distortion, but in the final track Hyvärinen gets his revenge as the two take turns exchanging blows.

Ilia Belorukov & Lauri Hyvärinen: Fix it if it ain’t Broken [Nunc]. Hyvärinen, recently heard on the cutting set of electric guitar duos with Jukka Kääriäinen Pulled Apart by Horses, pairs up with Belorukov’s modular synth. The shredding is more literal than usual, with Hyvärinen making extensive use of sampling pedals to feed his guitar into various mangling digital effects while Belorukov produces slabs of quasi-analogue noise. At times the guitar seems to act as a foil to the synth, or the two trade different flavours of electronic distortion, but in the final track Hyvärinen gets his revenge as the two take turns exchanging blows.

Ilia Belorukov / Nenad Marković: Signs of Suspicious Activity [Hera Corp.]. Belorukov’s modular synth again, this time with… trumpet. Marković is an equal match to the task, upsetting the balance by providing the white noise through various mutes to run interference on Belorukov’s loosey-goosey rambling on the opening track. Later they fall in together to produce some brooding, densely coloured scenes, but never get sombre enough to dispel the idea that one of them could take off at any moment, with either overdriven analogue feedback or a maundering semi-vocal line. The end duet is particularly fine, spinning out a wonky elegy where it’s never entirely clear which instrument is which.

Ilia Belorukov / Nenad Marković: Signs of Suspicious Activity [Hera Corp.]. Belorukov’s modular synth again, this time with… trumpet. Marković is an equal match to the task, upsetting the balance by providing the white noise through various mutes to run interference on Belorukov’s loosey-goosey rambling on the opening track. Later they fall in together to produce some brooding, densely coloured scenes, but never get sombre enough to dispel the idea that one of them could take off at any moment, with either overdriven analogue feedback or a maundering semi-vocal line. The end duet is particularly fine, spinning out a wonky elegy where it’s never entirely clear which instrument is which.

Pierre Borel: Katapult [Umlaut]. A set of jerky improvs for sax and drums, except that Borel’s been working intensively on playing both instruments at once. This one’s a bit of an outlier as there are no electronics involved, but I figure one-man-band counts as noise. A set of rules (left hand, right hand, etc.) guide how each instrument is to be deployed, a stricture placed upon an already limited combination that forces Borel into a more structured way of more thoroughly exploring what reduced potential exists. It gains seriousness as each piece drills down into the subtleties hidden inside such a simplistic formula, making for a curious little LP that’s not as fucking horrible as you first feared.

Pierre Borel: Katapult [Umlaut]. A set of jerky improvs for sax and drums, except that Borel’s been working intensively on playing both instruments at once. This one’s a bit of an outlier as there are no electronics involved, but I figure one-man-band counts as noise. A set of rules (left hand, right hand, etc.) guide how each instrument is to be deployed, a stricture placed upon an already limited combination that forces Borel into a more structured way of more thoroughly exploring what reduced potential exists. It gains seriousness as each piece drills down into the subtleties hidden inside such a simplistic formula, making for a curious little LP that’s not as fucking horrible as you first feared.

Jorge Espinal: Bombos y cencerros [Buh]. Guitarist Espinal plays bass drum, cowbell and sampler all simultaneously (not again!) with his usual axe. The samples are mostly percussion, both latin and drum machine, with all the pieces having a strong emphasis on overlaid incongruous rhythms (yes, again). Despite my unfortunate phrasing, this is not a derivative set of pieces, even as they twist ideas of “Latin” into alien thuds and burbles. The polyrhythmic idea is so distorted into something new that anyone ignorant of Latin American music (raises hand) won’t suspect it’s there. While that’s going on, Espinal sneaks in some witty blunt-fingered take-offs of more fluid guitar-pickers, but I won’t saddle him with the sobriquet of the Peruvian Eugene Chadbourne. Unless he also makes dick jokes.

Jorge Espinal: Bombos y cencerros [Buh]. Guitarist Espinal plays bass drum, cowbell and sampler all simultaneously (not again!) with his usual axe. The samples are mostly percussion, both latin and drum machine, with all the pieces having a strong emphasis on overlaid incongruous rhythms (yes, again). Despite my unfortunate phrasing, this is not a derivative set of pieces, even as they twist ideas of “Latin” into alien thuds and burbles. The polyrhythmic idea is so distorted into something new that anyone ignorant of Latin American music (raises hand) won’t suspect it’s there. While that’s going on, Espinal sneaks in some witty blunt-fingered take-offs of more fluid guitar-pickers, but I won’t saddle him with the sobriquet of the Peruvian Eugene Chadbourne. Unless he also makes dick jokes.

Beat Keller & Jukka Kääriäinen: Birds of All Kinds [Bokashi]. Kääriäinen, recently heard on the cutting set of electric guitar duos with Lauri Hyvärinen Pulled Apart by Horses, pairs up with Keller on second guitar. I know Keller only from his set of small, enigmatic string trios on Wandelweiser so it’s nice to hear he can make noise with the best of them. These are short, atmospheric live improvisations which nevetheless don’t stint on technique. Both use their guitars and effects as conduits, to direct and shape the sound they send flowing down the line to their amps. As the title suggests, plenty of feedback and harmonics but used as a jumping-off point to create something new. The thorough workouts are contained within short tracks to aid concentration. They’re not averse to getting rowdy at times, and occasionally will pluck notes on the strings.

Beat Keller & Jukka Kääriäinen: Birds of All Kinds [Bokashi]. Kääriäinen, recently heard on the cutting set of electric guitar duos with Lauri Hyvärinen Pulled Apart by Horses, pairs up with Keller on second guitar. I know Keller only from his set of small, enigmatic string trios on Wandelweiser so it’s nice to hear he can make noise with the best of them. These are short, atmospheric live improvisations which nevetheless don’t stint on technique. Both use their guitars and effects as conduits, to direct and shape the sound they send flowing down the line to their amps. As the title suggests, plenty of feedback and harmonics but used as a jumping-off point to create something new. The thorough workouts are contained within short tracks to aid concentration. They’re not averse to getting rowdy at times, and occasionally will pluck notes on the strings.

Cecilia Lopez and Wenchi Lazo: Desposable [Tripticks Tapes]. Some more weirdo synth noodling and what sound like electronically drenched drums but are apparently produced on a drum machine. The synth patches chatter away amongst themselves, held together by a drum machine that drifts out of noise and into something uncanny; it sounds that way probably because the drum patches eschew the usual kick bass and hi-hats for resonant but trebly snares and traps, with occasional excursions into off-grid rolls. After a while it all coalesces into sort of a riff that sustains the momentum, before falling apart again as the musicians switch roles. The flip side offers am alternative take on the same, with the difference being on how long it takes to get into the groove.

Cecilia Lopez and Wenchi Lazo: Desposable [Tripticks Tapes]. Some more weirdo synth noodling and what sound like electronically drenched drums but are apparently produced on a drum machine. The synth patches chatter away amongst themselves, held together by a drum machine that drifts out of noise and into something uncanny; it sounds that way probably because the drum patches eschew the usual kick bass and hi-hats for resonant but trebly snares and traps, with occasional excursions into off-grid rolls. After a while it all coalesces into sort of a riff that sustains the momentum, before falling apart again as the musicians switch roles. The flip side offers am alternative take on the same, with the difference being on how long it takes to get into the groove.

J.L. Maire / Alfredo Costa Monteiro: Estelas [Hera Corp.]. Monteiro’s earlier solo work Suspension pour une perte was relentlessly sombre, an impression initially sustained here by the invocation of tombs and monuments. For this album he works with Maire on analogue synth with electronics and opens up the soundworld to greater effect. This is a pair of fearsome soundscapes, sufficient variety in coloration and texture to make them all the more momentous. The reverb is heavy but provides a sense of space and distance, the first track in particular sustaining monumental presence with an added chill of foreboding. The second piece is arguably looser, adding greater diversity of sounds to produce more drama at the expense of consistency.

J.L. Maire / Alfredo Costa Monteiro: Estelas [Hera Corp.]. Monteiro’s earlier solo work Suspension pour une perte was relentlessly sombre, an impression initially sustained here by the invocation of tombs and monuments. For this album he works with Maire on analogue synth with electronics and opens up the soundworld to greater effect. This is a pair of fearsome soundscapes, sufficient variety in coloration and texture to make them all the more momentous. The reverb is heavy but provides a sense of space and distance, the first track in particular sustaining monumental presence with an added chill of foreboding. The second piece is arguably looser, adding greater diversity of sounds to produce more drama at the expense of consistency.

Merzbow: Sedonis [Signal Noise]. I’ve heard of this guy. For my whole life spent in Ugly Music, Merzbow has been ubiquitous to the point of inevitability and so, much like trouble, I’ve never bothered to seek it out, figuring it would come to me sooner or later. Thankfully this has never happened until now and I’m glad it’s Merzbow who found me first. Someone’s gonna pipe up and say it’s not a patch on some of his other 9000 albums but I really liked it. He’s got protean, impulsive noisemaking down to a finely balanced skill, with Sedonis serving up dense sonic tableaux that are simultaneously bombastic and intricate. The multilayering overwhelms you with complexity and information overload, instead of bludgeoning you with excess.

Merzbow: Sedonis [Signal Noise]. I’ve heard of this guy. For my whole life spent in Ugly Music, Merzbow has been ubiquitous to the point of inevitability and so, much like trouble, I’ve never bothered to seek it out, figuring it would come to me sooner or later. Thankfully this has never happened until now and I’m glad it’s Merzbow who found me first. Someone’s gonna pipe up and say it’s not a patch on some of his other 9000 albums but I really liked it. He’s got protean, impulsive noisemaking down to a finely balanced skill, with Sedonis serving up dense sonic tableaux that are simultaneously bombastic and intricate. The multilayering overwhelms you with complexity and information overload, instead of bludgeoning you with excess.

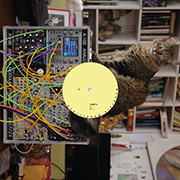

Mauricio Moquillaza: Mauricio Moquillaza [Buh]. Ey up, it’s another Peruvian. The Buh label has been sending me these so expect to read more about them in the future. Haven’t looked up anything about Moquillaza’s background but this is his first solo release. Four works for modular synth which ease back and forth in a disconcertingly nonchalant fashion from energetic sequencer burbles to washes of abrasive noise. By the last track, when he almost fully embraces space rock which has been implied all along, it feels less like settling into a comfort zone and more like finding a new destination. It all sounds very experienced and polished, but apparently each track is a single take.

Mauricio Moquillaza: Mauricio Moquillaza [Buh]. Ey up, it’s another Peruvian. The Buh label has been sending me these so expect to read more about them in the future. Haven’t looked up anything about Moquillaza’s background but this is his first solo release. Four works for modular synth which ease back and forth in a disconcertingly nonchalant fashion from energetic sequencer burbles to washes of abrasive noise. By the last track, when he almost fully embraces space rock which has been implied all along, it feels less like settling into a comfort zone and more like finding a new destination. It all sounds very experienced and polished, but apparently each track is a single take.

Rick Reed: The Symmetry of Telemetry [Elevator Bath / Sedimental]. I’m told Reed is a veteran of the Austin experimental scene in Texas and there’s an old-school feeling to the three electronic works presented here. Composed around 2020 using Buchlas and Moogs, the sounds have fuzzy edges not heard in typical digital soundfiles. Reed uses a subdued colour palette throughout (don’t let his artwork on the cover foll you) and everything sounds a bit muted and distant. Seemingly going for ambient mood, yet each piece progresses according to a pulse that’s a little too neat, which stunts the effect. Each of the two longer works ends with snatches of radio speech mixed into the background, making the whole exercise sound a little tired.

Rick Reed: The Symmetry of Telemetry [Elevator Bath / Sedimental]. I’m told Reed is a veteran of the Austin experimental scene in Texas and there’s an old-school feeling to the three electronic works presented here. Composed around 2020 using Buchlas and Moogs, the sounds have fuzzy edges not heard in typical digital soundfiles. Reed uses a subdued colour palette throughout (don’t let his artwork on the cover foll you) and everything sounds a bit muted and distant. Seemingly going for ambient mood, yet each piece progresses according to a pulse that’s a little too neat, which stunts the effect. Each of the two longer works ends with snatches of radio speech mixed into the background, making the whole exercise sound a little tired.

Tetrao Tetrix: Nyctalopia [Bruit]. Gaudenz Badrutt returns, joined by Jean-Luc Guionnet on alto sax and Frantz Loriot on viola (huh?). It’s improv I guess, with some ground rules and a focus on the quality of sound over matters of phrasing, structure or texture. The most notable aspect is the presence of silence, pervasive throughout and implicit as a ingredient to the mix even when all three are playing. This what transforms each of the six tracks away from the sound of musicians playing to that of electroacoustic composition, particularly in the earlier parts where the three work together as a single force. By the end the overall intention remains, but the emphasis shifts to each playing for themselves, which in this context feels like losing control.

Tetrao Tetrix: Nyctalopia [Bruit]. Gaudenz Badrutt returns, joined by Jean-Luc Guionnet on alto sax and Frantz Loriot on viola (huh?). It’s improv I guess, with some ground rules and a focus on the quality of sound over matters of phrasing, structure or texture. The most notable aspect is the presence of silence, pervasive throughout and implicit as a ingredient to the mix even when all three are playing. This what transforms each of the six tracks away from the sound of musicians playing to that of electroacoustic composition, particularly in the earlier parts where the three work together as a single force. By the end the overall intention remains, but the emphasis shifts to each playing for themselves, which in this context feels like losing control.

Filed under: Music, Reviews by Ben.H

Tags: Aaron Quinn, Alfredo Costa Monteiro, Beat Keller, Cecilia Lopez, Frantz Loriot, Gaudenz Badrutt, Ilia Belorukov, Ishmael Ali, J.L. Maire, Javier Areal Vélez, Jean-Luc Guionnet, Jorge Espinal, Jukka Kääriäinen, Lauri Hyvärinen, Mauricio Moquillaza, Merzbow, Nenad Marković, Pierre Borel, Rick Reed, Tetrao Tetrix, Wenchi Lazo

No Comments »

Catching up on guitars, mostly

Tuesday 25 March 2025

Yes I fell off the posting wagon again and now I’m going through the pile of stuff I’ve been meaning to write about and gosh there’s a whole lot of stuff with guitars. I’m not going to cover all of them: this is just a selection. There’s a solo improv live set from Eldritch Priest, which you would kind of expect but also not expect if you heard his Omphaloskepsis from a little while back. Dormitive Virtue [Halocline Trance] is a neat little album of electric guitar which promises to be an informative but derivative curiosity, only to turn into an informative but beguiling curiosity. You know the drill: one-off solo show in small venue, “a friend cajoled him into releasing” yada yada and the album starts out with a typically abrasive, discontinuous riff on discordant melodies from this composer. Except it’s not typical; after the opening fake-out comes a wistul, bluesey jazz rumination which sets the tone for the rest of the album. When distorted sounds reappear, they gain a reverberant sheen of moody atmospherics; the shorter improvisations are endearingly charming or endearingly playful. The pre-composed pieces focus on melody alone, retaining a gentle feel even at their most angular. His take on Wayne Shorter’s Iris makes room for small asides as elaboration, providing an insight into his own compositional ideas.

Yes I fell off the posting wagon again and now I’m going through the pile of stuff I’ve been meaning to write about and gosh there’s a whole lot of stuff with guitars. I’m not going to cover all of them: this is just a selection. There’s a solo improv live set from Eldritch Priest, which you would kind of expect but also not expect if you heard his Omphaloskepsis from a little while back. Dormitive Virtue [Halocline Trance] is a neat little album of electric guitar which promises to be an informative but derivative curiosity, only to turn into an informative but beguiling curiosity. You know the drill: one-off solo show in small venue, “a friend cajoled him into releasing” yada yada and the album starts out with a typically abrasive, discontinuous riff on discordant melodies from this composer. Except it’s not typical; after the opening fake-out comes a wistul, bluesey jazz rumination which sets the tone for the rest of the album. When distorted sounds reappear, they gain a reverberant sheen of moody atmospherics; the shorter improvisations are endearingly charming or endearingly playful. The pre-composed pieces focus on melody alone, retaining a gentle feel even at their most angular. His take on Wayne Shorter’s Iris makes room for small asides as elaboration, providing an insight into his own compositional ideas.

I heard Francesco Serra’s close study of empty space Guest Room a few years ago and was taken by it’s use of resonance and sympathetic vibrations. His new work Personal [i dischi di angelica] is a work of similar protracted research in a given space, but this time the focus is on solo acoustic guitar. Nothing fancy, just plucking and strumming that thing with no apparent direction or purpose. It would appear that the focus is meant to be on the sound of the guitar, but the playing style doesn’t reorient the listener’s attention to the acoustics; it just trundles along in a familiar way until it’s just hanging around in the background. The use of resonating snare drums comes later but it feels a little like a forced intervention to make things more interesting. Things actually do get a little more interesting when the guitar disappears, leaving a quiescent field recording that eventually acquires an overlay of buzzing e-bowed strings. This would work as a mysterious, shadowy counterpart to the first half of the album if the whole setup hadn’t been so protracted and innocuous.

I heard Francesco Serra’s close study of empty space Guest Room a few years ago and was taken by it’s use of resonance and sympathetic vibrations. His new work Personal [i dischi di angelica] is a work of similar protracted research in a given space, but this time the focus is on solo acoustic guitar. Nothing fancy, just plucking and strumming that thing with no apparent direction or purpose. It would appear that the focus is meant to be on the sound of the guitar, but the playing style doesn’t reorient the listener’s attention to the acoustics; it just trundles along in a familiar way until it’s just hanging around in the background. The use of resonating snare drums comes later but it feels a little like a forced intervention to make things more interesting. Things actually do get a little more interesting when the guitar disappears, leaving a quiescent field recording that eventually acquires an overlay of buzzing e-bowed strings. This would work as a mysterious, shadowy counterpart to the first half of the album if the whole setup hadn’t been so protracted and innocuous.

Maybe it’s because I’ve also been listening to Varvara [self-released], a solo work by guitarist/composer Àlex Reviriego. The presence of a steel-stringed acoustic is also the central force here, but its role is much more complex. The crystalline acoustic sounds are sampled, apparently, and become the motivator for a deeply-textured web of drones and unpitched noise. The use of feedback loops and empty circuits play an important role here, creating evocative backdrops which assume greater prominence as the guitar fades away, with an inherent instability that nudges the wash of sound into darker and more disturbing moods. When the guitar reappears in part two, it has become enmeshed within the electronic noise, partly driving the drones while also acting as an armature for the increasingly alien soundscape. Despite this, the plucked strings never sound incongruous with the heavy synthesised sounds, thus making the resultant work even stranger. If that’s not enough for your to chew on, remember that this is only the second volume of Reviriego’s projected tetralogy of guitar pieces “inspired by the virgin martyrs of the early Christian church”.

Maybe it’s because I’ve also been listening to Varvara [self-released], a solo work by guitarist/composer Àlex Reviriego. The presence of a steel-stringed acoustic is also the central force here, but its role is much more complex. The crystalline acoustic sounds are sampled, apparently, and become the motivator for a deeply-textured web of drones and unpitched noise. The use of feedback loops and empty circuits play an important role here, creating evocative backdrops which assume greater prominence as the guitar fades away, with an inherent instability that nudges the wash of sound into darker and more disturbing moods. When the guitar reappears in part two, it has become enmeshed within the electronic noise, partly driving the drones while also acting as an armature for the increasingly alien soundscape. Despite this, the plucked strings never sound incongruous with the heavy synthesised sounds, thus making the resultant work even stranger. If that’s not enough for your to chew on, remember that this is only the second volume of Reviriego’s projected tetralogy of guitar pieces “inspired by the virgin martyrs of the early Christian church”.

Erica Dawn Lyle’s cassette for Notice Recordings also captures her working through some stuff. The two parts of Colonial Motels are extreme studies on the use of the amplifier’s tremolo knob. Once again, improvisations with single unedited takes, using looping effects to build up layers of choppy sounds which are then sculpted on the fly into quasi-melodic squalls before gusting into walls of torrential noise. The strange overall effect is the way it skips and skitters along, propelling itself through the obnoxious loudness without ever resorting to rocking out to retain each performance’s shape or momentum.

Erica Dawn Lyle’s cassette for Notice Recordings also captures her working through some stuff. The two parts of Colonial Motels are extreme studies on the use of the amplifier’s tremolo knob. Once again, improvisations with single unedited takes, using looping effects to build up layers of choppy sounds which are then sculpted on the fly into quasi-melodic squalls before gusting into walls of torrential noise. The strange overall effect is the way it skips and skitters along, propelling itself through the obnoxious loudness without ever resorting to rocking out to retain each performance’s shape or momentum.

Yaron Deutsch titling his album Soul, Soul, Soul, Sweet Soul. [self-released] really doesn’t prepare you for the music here. As with Lyle and Serra, Deutsch is working out some ideas here, taking his work with other musicians as launch-points for solo excursions. Sanen Song began as a solo played over a sound installation piece by Helena Persson; Sub_Current is Deutsch’s solo part for an electric guitar concerto by Stefan Prins spun off on its own; Greetings from Astridplein takes a recording of Deutsch and Tom Pauwels playing a duet by Matthew Shlomowitz and cuts in urban field recordings. Sanen Song begins with atmospheric high drones before becoming increasingly busy with fiddly little arpeggiations and capricious pitch-shifting, while Sub_Current throws distorted power chords into a blender of pitch-bending and tone-switching, restlessly hopping between swatches of slowed-down white noise and cartoonish bendy-stretchy pedal work. Both works show invention, but their emphasis on technique suggests that they would be of more interest to other guitarists than listeners in general. Greetings from Astridplein is a nice little vignette that makes me want to hear Shlomowitz’s piece in its original form: it’s titled Hocket for Dylan & Alan.

Yaron Deutsch titling his album Soul, Soul, Soul, Sweet Soul. [self-released] really doesn’t prepare you for the music here. As with Lyle and Serra, Deutsch is working out some ideas here, taking his work with other musicians as launch-points for solo excursions. Sanen Song began as a solo played over a sound installation piece by Helena Persson; Sub_Current is Deutsch’s solo part for an electric guitar concerto by Stefan Prins spun off on its own; Greetings from Astridplein takes a recording of Deutsch and Tom Pauwels playing a duet by Matthew Shlomowitz and cuts in urban field recordings. Sanen Song begins with atmospheric high drones before becoming increasingly busy with fiddly little arpeggiations and capricious pitch-shifting, while Sub_Current throws distorted power chords into a blender of pitch-bending and tone-switching, restlessly hopping between swatches of slowed-down white noise and cartoonish bendy-stretchy pedal work. Both works show invention, but their emphasis on technique suggests that they would be of more interest to other guitarists than listeners in general. Greetings from Astridplein is a nice little vignette that makes me want to hear Shlomowitz’s piece in its original form: it’s titled Hocket for Dylan & Alan.

On the other hand, Lauri Hyvärinen and Jukka Kääriäinen’s guitar duets on Pulled Apart by Horses [Bokashi] are just as relaxed and soothing as the title would have you believe. First of all, the prospect of an album of two electric guitars and nothing else should be enough to set your teeth on edge. It does, but in the most delightful way: the five tracks here are shot through with freewheeling exuberance and malicious glee. Hyvärinen and Kääriäinen maintain a knife-edge balance of calculated spontaneity, coming up with a dizzying array of sounds that never stick around too long as they careen from one idea to another without sticking in one place too long. It’s bracing but it’s more fun than most of these types of excursions.

On the other hand, Lauri Hyvärinen and Jukka Kääriäinen’s guitar duets on Pulled Apart by Horses [Bokashi] are just as relaxed and soothing as the title would have you believe. First of all, the prospect of an album of two electric guitars and nothing else should be enough to set your teeth on edge. It does, but in the most delightful way: the five tracks here are shot through with freewheeling exuberance and malicious glee. Hyvärinen and Kääriäinen maintain a knife-edge balance of calculated spontaneity, coming up with a dizzying array of sounds that never stick around too long as they careen from one idea to another without sticking in one place too long. It’s bracing but it’s more fun than most of these types of excursions.

There’s been much deserved attention for Jules Reidy’s latest album Ghost/Spirit, which makes last year’s Instants & Their Echoes [Hospital Hill] seem slept on by comparison. It’s the most surprising of the lot here, not least because of the relative absence of Reidy’s trademark guitar. A pair of self-similar works, commissioned by the brass trio Zinc & Copper (Hilary Jeffery, trumpet and trombone; Elena Kakaliagou, French horn; Robin Hayward, tuba), Instants & Their Echoes is a real ear-opener, one that reveals a new perspective on Reidy as a composer. The brass plays softly, in just intonation, building up overlapping harmonies into gently separated moments, set within a web of slowly cascading electronic tones. Reidy’s guitar can also be heard on occasion, deep in the mix to add to the glistening electronic timbres. Sounds have been extended and lowered in pitch to create reflections and imitations, that disorient while also implying a loose canonic structure that holds the piece together. It’s very spacious, in a floaty, dreamy way, as brass and gutar will periodically drop away and let the electronics sustain the mood in self-contemplation. There’s a confidence in the way the music starts and ends, twice, tinting the air and the time it takes with its sound and then withdraws without the need for justification, leaving a deep aural after-image in the mind.

There’s been much deserved attention for Jules Reidy’s latest album Ghost/Spirit, which makes last year’s Instants & Their Echoes [Hospital Hill] seem slept on by comparison. It’s the most surprising of the lot here, not least because of the relative absence of Reidy’s trademark guitar. A pair of self-similar works, commissioned by the brass trio Zinc & Copper (Hilary Jeffery, trumpet and trombone; Elena Kakaliagou, French horn; Robin Hayward, tuba), Instants & Their Echoes is a real ear-opener, one that reveals a new perspective on Reidy as a composer. The brass plays softly, in just intonation, building up overlapping harmonies into gently separated moments, set within a web of slowly cascading electronic tones. Reidy’s guitar can also be heard on occasion, deep in the mix to add to the glistening electronic timbres. Sounds have been extended and lowered in pitch to create reflections and imitations, that disorient while also implying a loose canonic structure that holds the piece together. It’s very spacious, in a floaty, dreamy way, as brass and gutar will periodically drop away and let the electronics sustain the mood in self-contemplation. There’s a confidence in the way the music starts and ends, twice, tinting the air and the time it takes with its sound and then withdraws without the need for justification, leaving a deep aural after-image in the mind.

Filed under: Music, Reviews by Ben.H

Tags: Àlex Reviriego, Eldritch Priest, Erica Dawn Lyle, Francesco Serra, Jukka Kääriäinen, Jules Reidy, Lauri Hyvärinen, Yaron Deutsch

1 Comment »

Guitar? Solos? Fredrik Rasten, Lauri Hyvärinen

Saturday 16 April 2022

I guess there is still a lot more that can be done with guitars; as with pianos in previous centuries, the synergy between artistic creativity and technological development is prodigious. It’s still a bit of a mystery what exact role technology plays in Fredrik Rasten’s solo album on Insub Svevning, where what sounds like an electric guitar is not. When previously heard in his collaboration with Vilhelm Bromander, Rasten’s guitar was mostly bowed to produce complex overtones. Here, everything is plucked and, while the overtones are simpler, they predominate. Svevning is two prolonged studies in arpeggiation, each successive note combining with the last to produce beating frequencies. There’s tremendous sustain in the harmonics, which suggest they have been electronically induced, yet Rasten also sings pitches against the guitar to extend and perturb the resonance of the strings. Despite the technical emphasis on psychoacoustic phenomena, a different effect takes over as content is subsumed by duration. With each piece running to forty minutes, the consistency becomes mesmerising for the listener while it becomes wearying for the player, leading to turns in the course of the music that suggest human need over theory.

I guess there is still a lot more that can be done with guitars; as with pianos in previous centuries, the synergy between artistic creativity and technological development is prodigious. It’s still a bit of a mystery what exact role technology plays in Fredrik Rasten’s solo album on Insub Svevning, where what sounds like an electric guitar is not. When previously heard in his collaboration with Vilhelm Bromander, Rasten’s guitar was mostly bowed to produce complex overtones. Here, everything is plucked and, while the overtones are simpler, they predominate. Svevning is two prolonged studies in arpeggiation, each successive note combining with the last to produce beating frequencies. There’s tremendous sustain in the harmonics, which suggest they have been electronically induced, yet Rasten also sings pitches against the guitar to extend and perturb the resonance of the strings. Despite the technical emphasis on psychoacoustic phenomena, a different effect takes over as content is subsumed by duration. With each piece running to forty minutes, the consistency becomes mesmerising for the listener while it becomes wearying for the player, leading to turns in the course of the music that suggest human need over theory.

Meanwhile, Intonema have released a solo album by Finnish guitarist Lauri Hyvärinen. Cut Contexts crops selections of the guitarist’s practice over the past two years of Covid retreat, presenting a set of five scenes of aural portraiture. Guitar playing is heard as a work in progress and as an activity in place, a given situation subject to transformation. While the guitar here might focus on technique, the emphasis is shifted by the locating presence of environmental sounds and by relocating device of setting each piece into a seven-minute window of time, framed by silence as needed. It creates a kind of cubist presentation, in which the often cosy domesticity of the subject matter is skewed by an oblique depiction in strictly formal terms. The method neatly excises the potential self-indulgence of the diary format that lurks beneath other pandemic documentaries. Why are there not seven pieces? Probably because that would be too many.

Meanwhile, Intonema have released a solo album by Finnish guitarist Lauri Hyvärinen. Cut Contexts crops selections of the guitarist’s practice over the past two years of Covid retreat, presenting a set of five scenes of aural portraiture. Guitar playing is heard as a work in progress and as an activity in place, a given situation subject to transformation. While the guitar here might focus on technique, the emphasis is shifted by the locating presence of environmental sounds and by relocating device of setting each piece into a seven-minute window of time, framed by silence as needed. It creates a kind of cubist presentation, in which the often cosy domesticity of the subject matter is skewed by an oblique depiction in strictly formal terms. The method neatly excises the potential self-indulgence of the diary format that lurks beneath other pandemic documentaries. Why are there not seven pieces? Probably because that would be too many.