Back in 2009 I wrote a blog post titled The mystery of Julius Eastman’s Creation:

When a forgotten talent is rediscovered, it’s sobering to realise how little time it takes for the biographical details of an artist to become as elusive and conjectural as those of a Jacobean playwright.

The fate of the composer Julius Eastman, not yet twenty years dead, is an extreme but illustrative example. Mary Jane Leach has been on a quest for ten years to gather up whatever scattered fragments of his work have survived. Devoid of context, the stray odds and ends can be frustratingly hard to fit into place.

The post went on to discuss how I’d found online a 1973 recording of a piece attributed to Eastman, titled Creation. The piece was dated 1954; if this was correct, Eastman would have been 14 when he wrote it. I could find no other reference on the web to this piece’s existence, other than a 1974 radio guide mentioning the same recording. Leach’s site dedicated to Eastman didn’t list it amongst his known works. Was the piece I’d heard really by Eastman? Had it been mistitled? Was it really from 1954?

Leach’s site has been frequently updated since then and Creation is listed, with a description matching the recording and appropriately dated 1973. A mere seven years ago I would have to have sought out and gained access to every dusty archive in London, searching for evidence of an old Belgian radio broadcast, and even then I probably wouldn’t have been able to verify that this piece even existed.

(In that 2009 post, see the comment left by Daniel Wolf. The process of piecing together the fragments goes on.)

Filed under: Music by Ben.H

1 Comment »

The Presence of Julius Eastman

Tuesday 20 December 2016

For four years now, the London Contemporary Music Festival have put together the most exciting new music events in town. After last year’s eclectic extravaganza, LCMF 2016 was tightly focused and all the more revelatory for it. Three nights in another new venue (with a surprisingly good sound) dedicated to the work of Julius Eastman.

Eastman died in 1990, in almost total obscurity. Since the turn of the century, Mary Jane Leach has led a quest to rediscover, salvage and revive what remains of his music. Most Eastman fans probably first heard of him through the 3-CD set that resulted from this hunt for recordings, released ten years ago. The recovery process still goes on today: this year Frozen Reeds issued a tape of the large-scale work Femenine that had laid dormant for 40 years. These recordings reclaimed a lost strand of minimal music that was never fully pursued; a unique, vital voice in a style of composition that had seemed exhausted.

Over the last weekend, it became abundantly clear that these records were just scratching the surface, both in what listeners know about Eastman’s music and in how much more there is still to be revealed in his “classics”. Six pieces by Eastman were played, one of them a world premiere. That 1984 piece, Hail Mary for voice and piano, is still not mentioned on Leach’s list of known works. For a bit of perspective, Leach’s essay from 2004 mentions that she has obtained copies of scores for only two and a half works.

The rediscovered recordings have obtained something of an aura, of essential documents from a lost moment in time. The LCMF gigs refuted that idea and firmly established Eastman as a composer in a living history of music-making. Performed live by understanding, talented musicians, the pieces took on a life of their own, with greater emotional depth and pure sensory delight than can be found in the old tapes. This was most clear in the ensemble works. Apartment House’s Femenine benefited from greater accuracy and confidence, which allowed its increasingly outrageous digressions to hit the audience with an almost overwhelming force. Stay On It finally, actually sounded like a kindred work to the jazz and R&B Eastman spoke of. Other versions I’ve heard sound like a classic minimal composition derailed by an awkwardly sectional structure. At LCMF it really did start to heave and glide from one idea to another, subverting its lock-groove origins and risking anarchy, knowing it’s more fun to hang with Sun Ra than Steve Reich.

As the pianist Philip Thomas mentioned afterwards, “Julius Eastman’s music is music to be performed, heard, experienced and understood via the particular energies of live performance…. Nothing much to hold on to but everything to play with. So much revealed in the playing.” Special mention needs to go to vocalist Elaine Mitchener, whose free-form improvisation over Stay On It set the tone and led the work into new territory.

Mitchener’s voice also added a raw, disquieting edge to the otherwise hushed and restrained later works, Hail Mary and Buddha. The two pieces are almost unknown and I’d like to hear them again to appreciate their subtleties. The works for multiple pianos (here played as two pianos eight hands), Evil Nigger and Gay Guerrilla, were played with a brilliant clarity. The seemingly straightforward process behind each one took on twists and turns, at once angry, elegiac, triumphant and defiant. The unexpected ways that Evil Nigger subsides into stillness and Gay Guerrilla seems to endlessly rise are both glorious and disturbing.

Other composers featured at these gigs were Arthur Russell and Frederic Rzewski. Russell and Eastman were collaborators and kindred spirits of sorts, both outsiders to “serious” (i.e. unengaged) music. Russell’s almost inaccessible Tower of Meaning received an all-too-rare airing, in a special chamber arrangement. Its otherworldly blankness points equally to medieval music, Satie’s Socrate and Cage’s Cheap Imitation of it, as well as much “naive” music of the late 20th Century.

The entire programme opened with Rzewski’s Coming Together; a key work in understanding Eastman’s musical approach – of minimal rhythms, harmonies and repetitions as a framework for looser improvisation – and his engagement with politics, revolution and their conflicts with his sexuality. These themes were pursued further on the second night when Rzewski himself performed his own De Profundis, a setting of Oscar Wilde’s text for reciting pianist. This was the other highlight of the Festival. Rzewski, now 78, may have faltered on occasion but his voice, playing and percussive gestures (including rapping on the piano lid, scratching himself, beating his skull with his fist) all spoke with an unmatched directness and clarity. It was a gripping performance, letting the words drive the music and the music serve the words.

Filed under: Music, Reviews by Ben.H

Tags: Arthur Russell, Frederic Rzewski, Julius Eastman

2 Comments »

More from the guitar: Sarah Hennies, d’incise, Cristián Alvear, Clara de Asís

Wednesday 14 December 2016

Earlier in the year I raved about Cristián Alvear’s album of Jürg Frey’s music for guitar. I’ve now been sent two new recordings by Alvear, again both for solo guitar. On the Frey album, I noticed Alvear’s intense concentration and colouration he brings to the sound of unamplified, classical guitar. These two new releases intensify that effect even further.

Appalachian Anatolia (14th century) is a 40-minute work for guitar by the Swiss composer d’incise. Like the Frey album, this has also been released on Another Timbre. It’s a curious piece, simultaneously very loose and tightly constrained. In his interview on the Another Timbre site d’incise mentions his unfamiliarity with the instrument. The score calls for the instrument’s sound to be modified in some way, yet also puts the onus on the performer to become familiar with recordings of other music: Machaut, various folk musics, Neil Young. Any resemblance to this music in the composition is detectable only from a highly distilled understanding of technique. The guitarist works through a series of small, closely-observed effects. The material is carefully limited and how it is used is left open to some interpretation. It’s casually thorough in its exploration of intonation, tone colour and external affects, in the way that Morton Feldman’s music is in exploring the space between semitones.

There’s a second recording of this piece, available as a free download through Insub. Clara de Asís plays Appalachian Anatolia (14th century) on an electric guitar. Both versions are clearly the same piece, with similar overall shape and disposition of material. When examined more closely, comparison of the two reveals striking differences, followed by unexpected similarities. Asís plays with sensitivity and imagination equal to Alvear, each finding ways to evoke sounds from their respective instruments that are obviously different in origin yet still clearly alike in their understanding of the music. As an example, Asís’ version ends with the quietest gestures set in a thin halo of feedback hum. Alvear ends in an equally muted way, allowing the acoustic instrument’s natural resonance to come to the foreground. If you like the Asís version, you’ll want to hear how Alvear interprets it, too.

The Mappa label “from a God‑forsaken place on south of Slovakia” has released another Cristián Alvear recording, of Sarah Hennies’ Orienting Response. This is another 40-minute solo workout, written for Alvear. It’s available as a download or, for some reason, a cassette in a wooden box. I don’t get the thing with cassettes these days, it seems so conspicuously materialistic. I’m sure being Slovakian isn’t an excuse.

The cassette format does mean, however, that you get two 42-minute performances of the one piece. It took me a while to work this out. It also took me a couple of listens to figure out that the piece was for solo acoustic guitar (I’d somehow got into my head it was a duo with harp) and the guitar was unmodified (I was getting confused with the d’incise). It was obviously thus my own fault for not being too impressed after the first listen: an unconnected sequence of dry, repetitious exercises. After correcting my mistakes and realising that I’d been hearing things that weren’t actually in the recording, I knew it needed to be listened to more closely.

In her notes, Hennies mentions attempting “the same kind of focus and intensity I have created with percussion instruments using an instrument (the nylon stringed guitar) that is naturally not well-equipped to produce the type of timbres or high dynamic levels that I have worked with up to this point.” Each of the six sections specifies a rigorous playing technique: “Play as accurately and consistently as possible but with the assumption that “mistakes” are inevitable.” Alvear’s eminently well-suited for this challenge; it makes the Frey and d’incise seem fanciful.

Strange paradox at work here: you’d expect that the better you are at playing it, the less interesting it would get. That doesn’t seem to be the case here. The substance of the piece is sufficiently stark that otherwise negligible differences become the subject of the music, much in the way that some of Alvin Lucier’s pieces work. The two performances here, seemingly identical at first, are in fact very close but quite distinct in detail and structural proportions. The score notes that “all timings and tempi are approximate and flexible”; I’m wondering how Alvear achieved this in performance.

Filed under: Music, Reviews by Ben.H

Tags: d'incise, Sarah Hennies

2 Comments »

Chain Of Ponds, Live. (+ new mp3)

Monday 12 December 2016

I want to thank Alexander Garsden and everyone involved in the Inland concert series in Australia. I had a great time, all the other musicians were cooler than me and they showed me you can still have late night fun in Melbourne if not in Sydney.

I’ve only just listened to the recordings from both shows now and my sets went about as well as I remembered. Performing live music from a laptop, without using the monitor screen, was a success and the pieces took on a life of their own when played in a way that allowed unexpected aspects of the sound to creep in.

I played three pieces from Chain Of Ponds, adapted for live performance. An album of studio performances is available on Bandcamp, but for these Australian gigs I decided to include new versions of some pieces that haven’t previously gone public.

I’ve uploaded a piece from the Melbourne gig – you should be able to stream or download it.

Chain Of Ponds: Thirteenth Pond (18 April 2015, take 1)

Filed under: Music, Self-promotion by Ben.H

1 Comment »

Last Weekend Just Past

Monday 5 December 2016

Sarah Hennies, Orienting Response (Cristián Alvear, guitar)

James Saunders, like you and like you (Ensemble Plus-Minus)

Kim Fowley, “The Trip”

Willie Tomlin, “Check Me Baby”

The Masked Marauders, “More Or Less Hudson’s Bay Again”

Eva-Maria Houben, orgelbuch (Eva-Maria Houben, organ)

Aretha Franklin, “Soulville”

György Kurtág, … quasi una fantasia…, op. 27 (Hermann Kretzschmar, piano; Ensemble Modern /Peter Eötvös)

Filed under: Music, Travel by Ben.H

No Comments »

Pauline Oliveros

Monday 28 November 2016

She made I of IV – one of my favourite pieces, a perfect union of conceptual elegance and wild inventiveness – and then decided there was more important stuff to be done. She kept exploring, from free group improvisations in the fifties, to the essential electronic works of the sixties and then on further into sonic meditations and deep listening, revealing more and more in music about how people can relate themselves to sound, both in hearing it and making it.

That’s a simplistic narrative, and the whole “deep listening” thing is less an endpoint to be venerated than an opening to another five decades of diverse approaches to music-making, informed by a equally wide-ranging conscientiousness of sound. I don’t admire all of it, but now that a little of that awareness has rubbed off on me I can never dismiss it. It ticks away at the back of my mind whenever I’m doing something musical. You don’t wonder if, but just how much, things in music would be different now if she had never been here.

Filed under: Music by Ben.H

No Comments »

Morphogenesis – Immediata

Monday 31 October 2016

You sometimes get the feeling that musicians these days are frightened of complexity. It seems to go back to the 1990s, when Pärt and Górecki captured the imaginations of a wider audience. Live musicians started to describe themselves as “lowercase”. Poor dead Feldman got conscripted to a bunch of causes. It’s still a big thing today.

I’m not saying it’s wrong, but sometimes you get the feeling that this hushed reverence for sound is an act of worship more out of fear than love. It’s nice then to hear musicians who aren’t trying to impress you with how damn much they care.

A bit over a year ago I heard Morphogenesis play their first live show since 2010. There was a piano, violin, tables of amplified objects, old cassette recorders, electronics ranging from the ingenious to the trashed. There were disputes, debates and openly aired doubts about the whole enterprise. One member resolved to perform entirely from his car parked outside the venue. The audience loved it: the music was always alive, filled with ungraspable meanings and a self-destructive potential that never dissipated. After more protracted debate, a recording of the event has been released on Otoroku. It sounds as good as I remembered, probably because enough time has passed that I can no longer recollect details.

A bit over a year ago I heard Morphogenesis play their first live show since 2010. There was a piano, violin, tables of amplified objects, old cassette recorders, electronics ranging from the ingenious to the trashed. There were disputes, debates and openly aired doubts about the whole enterprise. One member resolved to perform entirely from his car parked outside the venue. The audience loved it: the music was always alive, filled with ungraspable meanings and a self-destructive potential that never dissipated. After more protracted debate, a recording of the event has been released on Otoroku. It sounds as good as I remembered, probably because enough time has passed that I can no longer recollect details.

I talked a few weeks back about Anthony Pateras and Erkki Veltheim’s Entertainment = Control album, released on Pateras’ Immediata label. It’s one of a series of six CDs in which Pateras collaborates with other musicians in a way that renders the distinction between improvisation and composition irrelevant. The selections have been made from performances going back over 15 years. Each album comes with a transcribed conversation between the musicians, which are almost worth the price alone.

I talked a few weeks back about Anthony Pateras and Erkki Veltheim’s Entertainment = Control album, released on Pateras’ Immediata label. It’s one of a series of six CDs in which Pateras collaborates with other musicians in a way that renders the distinction between improvisation and composition irrelevant. The selections have been made from performances going back over 15 years. Each album comes with a transcribed conversation between the musicians, which are almost worth the price alone.

Subjects of interest crop up again and again: politics, money, sex. These aren’t presented as public statements of ideology (what was once the preserve of Nono has now been delegated to Lily Allen) but as a discussion of the messy context in which this music has been made, the forces which have shaped it into its present form, streaming through your speakers.

In 2009 we all flew to Baden-Baden, most of which the Russian mafia has bought up for weekenders. The place itself radiates the deadness that accompanies concentrated wealth: everything is simultaneously pretty and rotten, and psychotherapy was booming.

When the sleeve notes of the ensemble Thymolphthalein’s album Mad Among The Mad begin like this, you know you’re back in a more tumultuous, plain spoken era, far removed from the bland comfort and complacency that these days is too often mistaken for professionalism. I’ve gone on about the sleeve notes so much because they reflect the music so well. The musicianship on all the discs is highly polished but the musical forms are new: as much a renunciation as an accommodation of the prevailing social, financial and cultural factors in which new music is made.

When the sleeve notes of the ensemble Thymolphthalein’s album Mad Among The Mad begin like this, you know you’re back in a more tumultuous, plain spoken era, far removed from the bland comfort and complacency that these days is too often mistaken for professionalism. I’ve gone on about the sleeve notes so much because they reflect the music so well. The musicianship on all the discs is highly polished but the musical forms are new: as much a renunciation as an accommodation of the prevailing social, financial and cultural factors in which new music is made.

Thymolphthalein was an electroacoustic ensemble working from a form of “systematized improvisation” (“Improv heads hated it, composers found it crass”). The sounds as well as the genres bleed into each other, a welter of details held taut in sharply-defined shapes. It all feels closely argued, enough to please a London Sinfonietta subscriber, with a confounding mix of electronics and technological manipulation that concert-hall composers are only just starting to catch up with. Occasionally there’s an outburst of mayhem to frighten the neighbours.

There’s more. Astral Colonels is an alter ego of Pateras and Valerio Tricoli, in which Tricoli has deconstructed and remixed improvisations between Pateras on various keyboards and Tricoli on open-reel tape recorders. The disc captures the feel of their old live shows, yet adds both complexity and space to the soundworld. The Long Exhale pairs piano and electronics with Anthony Burr on clarinet, in a set of carefully considered improvisations that focus inward on the sound of their instruments, as finely paced as a fully composed work without ever becoming reduced to the purely minimal.

There’s more. Astral Colonels is an alter ego of Pateras and Valerio Tricoli, in which Tricoli has deconstructed and remixed improvisations between Pateras on various keyboards and Tricoli on open-reel tape recorders. The disc captures the feel of their old live shows, yet adds both complexity and space to the soundworld. The Long Exhale pairs piano and electronics with Anthony Burr on clarinet, in a set of carefully considered improvisations that focus inward on the sound of their instruments, as finely paced as a fully composed work without ever becoming reduced to the purely minimal.

Filed under: Music, Reviews by Ben.H

No Comments »

Getting There: preparing for the next gig.

Thursday 27 October 2016

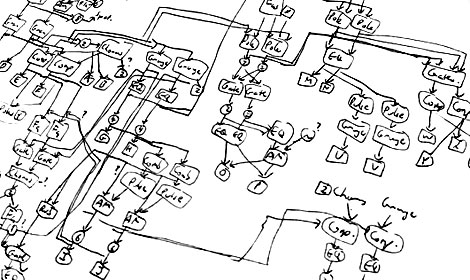

The original premise behind this piece was quite simple.

After some trial and error, a working model was hammered into shape.

A further year of development and the piece is now perfected.

The patch was constructed in AudioMulch, using only the components that come as standard with the software except for one freeware signal modeller at the very last stage.

In the above diagram it should be clear that there are no inputs to the system. None of the components play samples or generate signals. The patch is a network of interacting feedback circuits.

The network is played by sending MIDI instructions to the various controls on each component. During a performance, the system typically receives about 1000 MIDI commands per minute. To do this, I had to write a script that would generate a MIDI file containing all the instructions.

The script inserts commands and controller values according to (pseudo)random numbers. Randomness has to be used thoughtfully to get interesting, distinctive results, so a lot of revising, tweaking and polishing went into writing the script. The user can define basic parameters and bias weightings (duration, amount of activity) when the script is run.

The result?

Just now I’ve added another element: human intervention. For my upcoming live shows I will be playing these pieces directly from the patch and the script. Even when playing from the same score, the system will produce different sounds each time it is run: the score determines its behaviour, not its output. In the live shows I will be playing a MIDI controller to insert additional commands, which may have an immediate or delayed effect on the system.

Filed under: Music, Self-promotion by Ben.H

No Comments »

New gigs! Playing live in Australia real soon

Monday 24 October 2016

In a couple of weeks I’ll be travelling to Australia to play some live shows, as part of the Inland concert series.

I’ll be playing a specially-prepared live version of Chain Of Ponds, my piece for computer-generated feedback. Lucky punters will get to hear chance-determined feedback signals created right on the spot. A sample of what you’re in for can be heard on Bandcamp.

I’ll be in Melbourne on Thursday 10 November 2016, 8pm at the Church of All Nations, 180 Palmerston St, Carlton. The Sydney gig will be on Monday 14 November 2016, 8pm at Glebe Justice Centre, 37-47 St. Johns Road, Glebe. Both shows are packed with great musicians I can’t wait to hear.

Filed under: Music, Self-promotion by Ben.H

1 Comment »

Kammer Klang 2016-17: A Curmudgeon Writes

Friday 7 October 2016

The new season of Kammer Klang kicked off this week at Cafe Oto. It’s about the most innovative and interesting new music programme going around right now. It works by tapping into a genuine enthusiasm for music that pushes boundaries, for an audience ready and willing to take risks. You can build a following without dressing things up with gratuitous video projections or signalling towards pop music in hope of luring the cool kids.

Each month promises something different. Tuesday night began with Martyna Poznańska, who works with field recordings and videos. I recently went off on one about field recordings, and this gig reminded me of another problem I have with the genre. Too often, it can focus on techniques of documentation that struggle to find material which meets the aspirations of the artistic intention. Punters were treated to the overly-familiar ambient hum and views out the window that have become a hallmark of the medium.

A set of what might usually be considered more conventional “contemporary classical” music followed, from the fine ensemble Distractfold. The term ‘conventional’ is a relative term here as the violins and cellos were augmented with a battery of electronic signal processors large enough to max out the channels on the house PA. Sam Salem’s piece Untitled Valley of Fear used this excess of tech to build up a sufficiently murky and mysterious aural mood. Mauricio Pauly’s string trio Charred Edifice Shining both amplified and altered the instruments into an array of disrupting and disorientating effects. Overall, the piece felt a little too long and loose, as the reliance on unusual sounds could be edited and focused to maximise the impact. You wonder if the processing could have all been done on a laptop, with a fourth performer operating to spare the musicians the distraction of knob-twiddling.

The last set of the evening was with the composer Miles Cooper Seaton, who had been workshopping in the Cafe Oto Project Space around the corner for the past few days. His piece, Transient Music #2, began with his ensemble standing in a loose huddle around him in the centre of the room, all dressed in white like they were about to perform Stockhausen’s Ylem. Someone mentioned that this was going to be a sort of “deep listening” type deal. It started promisingly with a lengthy vocal solo by Cooper Seaton himself, in a speech that thanked and praised in turn everyone who had assisted and supported him during his stay, no matter how incidental their contribution may have been. Just as his peroration reached its apparent conclusion, he took a short breath and continued. And again. And again, without strain or effort, the flow of fine words continued. It was quite captivating; he is the Charlie Parker of panegyrics.

Sadly, modesty forced him to cut his solo short. For the remainder of the evening, members of the ensemble gingerly navigated amongst the punters around the room, playing an extended, gentle cadence on a leading tone.

Filed under: Music, Reviews by Ben.H

No Comments »

Serious Listening Weekend

Monday 3 October 2016

Are you playing an instrument or playing music? I’m old-fashioned enough to be leery of improvisation. Spent the weekend listening to new(ish) CDs of music that was not strictly composed; not in the authorial sense. For most of them I could make the argument that these are compositions, not improvisations.

There’s a growing, interesting genre of music that defines, develops and interprets compositional parameters as a joint process between musicians. These pieces aren’t an a priori realisation of a composer’s indeterminate score, nor are they spontaneously improvised. This seems to be a relatively recent phenomenon. Off the top of my head I can’t think of examples of these methods going back as far as “free improvisation” in the 1960s. There was “group composition” but that was just a term for improv musos who had to play art galleries instead of jazz clubs. It’s a sign that the genre is evolving, maturing.

I’ve been working through a rich vein of discs sent from the Another Timbre, Intonema and Immediata labels. Violinist Angharad Davies and pianist Tisha Mukarji recorded a set of improvisations over two days this February, released under the title ffansïon | fancies. In an interview on the website it mentions that the second day of recording was forced by “circumstances”, but this helped the album immensely. Material from the first day was evidently reworked, developed and refined for takes used on the final release. (“It struck me that this is a particularly fruitful way of using improvisation.”) The results show the benefit of additional time for reflection. Each piece reveals a focus on detail without losing sight of an overall direction or shape. Sounds are allowed to develop and change over time without rambling, giving each piece a character that can range from spiky pointillism to deconstructed folk music.

The St Petersburg-based Intonema label finds plenty of room to wander within what appears at first to be a pretty narrow range of music. The wandering is both musical and geographical. Tri presents a state-of-the-art improvisation in electroacoustic music with venerable electric guitarist Keith Rowe and Ilia Belorukov and Kurt Liedwart on various instruments, objects, computer processing and electronics. It documents a live performance and listening at home it’s hard to get too excited about all the technique on display. Sympathy to the guy in track one with the cough.

In contrast, Belorukov’s collaboration with Gaudenz Badrutt on electronics and “objects” and Jonas Kocher on accordion makes for fascinating listening. Rotonda is a live performance inside the Mayakovsky Library in St Petersburg. The musicians note that the space of the rotunda and its specific acoustics makes it “the fourth collaborator” in the piece. A compositional constraint is introduced: “acute attention to silences and extremely careful work with sound”. A slow, deliberately-paced music unfolds over nearly 50 minutes, each performer knowing that the resonance of the space will fill and colour their inactivity. A welcome relief from the horror vacui that affects so many musicians, without ever becoming a dry, didactic exercise in silence.

Tooth Car features Canadians Anne-F Jacques and Tim Olive playing live in the US: two fairly short extracts, which may be all that is needed for audio only. The limitations here are mechanical. Jacques constructs rotating surfaces that are played and amplified, while Olive amplifies other objects with magnetic pickups. The rotating devices provide regular ostinati throughout each piece and the various colours of metallic scraping suggest something close to sound sculpture.

For real group composition, Polis presents a combine, of intentional sounds and unexpected factors. Electroacoustic composers Vasco Alves, Adam Asnan and Louie Rice collaborated by preparing compositions and then mixed them, playing the mix through a car sound system that drove to various locations around the city of Porto. A complex but not impenetrable blending of sounds emerge, with different tracks overlapping each other, elaborated upon by different locations and live sampling of urban spaces. A neat convergence of pure sound, documentary, field recording and spatialisation.

Perhaps more conventional, Volume by the duo Illogical Harmonies on the Another Timbre label clearly identifies itself as a jointly composed piece. The violinist Johnny Chang and double bass player Mike Majkowski improvised together over several months, transcribing, performing and revising until they had sculpted this hour-long suite of five movements. This painstaking process has produced a beautifully restrained and focused performance, which at first sounds like a concentrated study on intonation and tuning but on closer listening reveals beautiful details of refined ornamentation and subtle relief.

Anthony Pateras has built a career out of being both a composer and an improviser, and his own Immediata label has recently produced a series of limited edition CDs of works that lurk in the grey area between the two domains. (Downloads are also available on Bandcamp.) I was going to discuss a couple of these now but I’ve just been listening again to his collaboration with Erkki Veltheim, Entertainment = Control. We’re back to straight violin and piano here and this bravura performance is part lost minimal epic, part social commentary, part virtuosic tour-de-force and part pisstake. I was going to say this disc is ideal if you think The Necks are too fussy or Charlemagne Palestine is too straightlaced, but then I started reading the extensive sleeve notes again. Pateras and Veltheim discuss fascism and sadomasochism, the Marx brothers, punk cabaret and the plague of El Sistema amongst other things and I can see I need to save all this for a separate post.

Filed under: Music, Reviews by Ben.H

Tags: Adam Asnan, Angharad Davies, Anne-F Jacques, Anthony Pateras, Erkki Veltheim, Gaudenz Badrutt, Ilia Belorukov, Illogical Harmonies, Johnny Chang, Jonas Kocher, Keith Rowe, Kurt Liedwart, Louie Rice, Mike Majkowski, Tim Olive, Tisha Mukarji, Vasco Alves

2 Comments »

This Is The New Music: 144 Pieces For Organ

Monday 19 September 2016

I’ve added another album to my Bandcamp store. The album costs £5, or you can download (most, not all) of the individual tracks individually for free. There are 144 tracks so you can feel like a big shot and pay for pure convenience. It’s about 90 minutes of music and the album comes with printable cover art, detailed sleeve notes and a video displaying attractive colour study scores for each piece.

I’ve added another album to my Bandcamp store. The album costs £5, or you can download (most, not all) of the individual tracks individually for free. There are 144 tracks so you can feel like a big shot and pay for pure convenience. It’s about 90 minutes of music and the album comes with printable cover art, detailed sleeve notes and a video displaying attractive colour study scores for each piece.

The 144 Pieces For Organ were composed in 2014, generated entirely from a set of formulas in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Think of them as musical snowflakes: each one a unique outcome from a single set of rules.

Filed under: Music, Self-promotion by Ben.H

No Comments »

Piano, Violin, Viola, Cello at Cafe Oto

Wednesday 14 September 2016

You wish Morton Feldman’s life hadn’t ended so soon; not least because his work was still revealing unknown territory. For all that his late works give the impression of having arrived upon a truly unique understanding of music, there’s always an element in them that suggests there’s still further to explore. Pieces from his last couple of years such as Coptic Light and For Samuel Beckett imply that he had distilled his musical language to an unbroken, monadic surface; but then his very last work, Piano, Violin, Viola, Cello, treats what’s gone before as a starting point for something new.

It had been played in London only once, 1999. Last night at Cafe Oto Mark Knoop, Aisha Orazbayeva, Bridget Carey and Anton Lukoszevieze played it for a second time. It was the hottest September day anyone could remember. Oto is a small concrete box with a bar up the back and passersby in the street just outside. The gig was sold out. For seventy-five minutes, we all sat or stood in stillness. It was an actual example of “if you build it, they will come”.

We stayed focused in the airless heat and humidity partly to avoid any excessive movement, mostly to follow the music, and partly out of respect for the imperturbable stoicism displayed by the musicians. You could see the conditions were taking their toll but they never let their heads drop. They carefully balanced their pacing and tone to enable the piece to unfold in a state of suspension, outside of typical musical concerns of linear time.

Feldman’s last piece draws on the lessons learned from his preceding work and wears its wisdom lightly. Its material is allowed to appear and evolve in what seems to be a more natural, organic way. For all the well appreciated subtleties of his music, the lack of obvious sections and cycled repetitions in this piece makes his other late works seem almost crude in comparison. When an obvious change is introduced – a short sequence of piano arpeggios, an exchange of pizzicato notes between the strings – it doesn’t come as a shock, but as the deepening of a plot. Each motif that appears, whether familiar or new, feels like a piece of a puzzle falling into place, revealing more of an image realised only on completion. The music feels more open, to the listener and to the world, without ever sacrificing its profound ambiguity of mood. Like John Cage’s best music, seeking to imitate nature, nothing’s a surprise but nothing is expected.

Filed under: Music, Reviews by Ben.H

Tags: Morton Feldman

3 Comments »

Eva-Maria Houben at Cafe Oto

Thursday 1 September 2016

A warm Tuesday night in London and Eva-Maria Houben is playing piano at Cafe Oto. She’s chosen to play three short sets, so people can enjoy the outside air, a drink and a chat, and refresh their focus on the music. Her music is typically slow and quiet, with a virtuosic use of silence. Such pieces can be very long, but not tonight. Two of the works are being played in public for the first time; one of them, Dandelion, is a loose collection of pages. Houben explains that it could go on “for hours” but tonight she’s selected just three pages to play.

Alex Ross, in the latest issue of the New Yorker, gives a good description of challenges and pleasures the new listener finds when discovering the Wandelweiser collective.

Eva-Maria Houben, a mainstay of the group, has written, “Music may exist ‘between’: between appearance and disappearance, between sound and silence, as something ‘nearly nothing.’”

He also observes the group’s “slightly cultish atmosphere” but this has started to fall away in recent years, as individual voices from within the group have become more recognisable. At Oto, Houben gives a short introduction to each piece, enthusiastically describing her inspirations. These sources are surprisingly diverse, as is her music.

She begins with another premiere, Tiefe – Depth for Piano. It’s a consummate study in decay and resonance. Isolated notes are struck and released immediately, held a short time and allowed to die away, sometimes being cut off, sometimes allowed to fade. Throughout the evening, there’s little use of the sustain pedal to colour, or cover, the frequent silences. Rather like Jürg Frey’s guitar music (another Wandelweiser composer), she sets the piano’s sounds within the surrounding silence and not against it.

Dandelion draws on prose inspiration rather than fixed notation, with the instrument’s strings mostly plucked by hand. For her Sonata for Piano No. 10 she explains how she was intrigued by Enescu’s talent for producing bell-like sonorities in his piano chords. The dedicatee for each movement is a very unWandelweiserish composer: Mussorgsky, Enescu, Schumann, Liszt, Messiaen. The semblance of each composer is evident in each movement’s set of tolling chords.

For all the emphasis on silence when describing this type of music, Houben gives particular attention to the piano’s capability for producing harmonic resonances and overtones (she refers to them as “partials”, suggesting a wish to complicate the instrument’s harmonic characteristics even further). In another work, the score is four pages of three lines each, single tones on a single stave in the treble. The piece ends with a long, steady drumming on a dense cluster of notes in the bass. The resonating strings produce a halo of high notes whistling over the top. No need for this low chord to be written down or on the music stand.

I still can’t get my head around this composer. The first pieces I heard seemed too bald – dependent on a theory, underdeveloped. Then I heard pieces which seemed much more warm-blooded to me. Others had a hint of veering into New Age meditation or whimsy, still others embrace tintinnabulation not unlike Arvo Pärt. Tonight, the music ranges from finely nuanced (Tiefe, Dandelion) to obsessively single-minded, as in the Sonata and another piece made entirely of single notes in groups of three, stacked end to end. Far removed from the sacerdotal austerity of Wandelweiser’s image, this is living, messy, human music.

Filed under: Music, Reviews by Ben.H

Tags: Eva-Maria Houben

1 Comment »

Violin+1: Bryn Harrison and Linda Catlin Smith

Monday 29 August 2016

First, I have to say that I had Linda Catlin Smith all wrong.

First, I have to say that I had Linda Catlin Smith all wrong.

A couple of months ago Another Timbre released four CDs under the general title ‘Violin+1’: four violinists, each in duet with a different type of musician. Two of the discs are of composed works, the other two are jointly composed between the musicians through improvisation. Violinist Aisha Orazbayeva and pianist Mark Knoop play a new work by Bryn Harrison, Receiving the Approaching Memory. I raved about Harrison’s monumental piano piece Vessels a couple of years ago, hearing it live and on CD. At the time I made the inevitable comparison to Morton Feldman’s late works, but noted significant differences. Unlike Feldman’s carpet-inspired patterns, Vessels was more like a vast labyrinth, beguiling in the way Tom Johnson’s An Hour For Piano or Josef Matthias Hauer can be.

Receiving the Approaching Memory takes these aspects of Vessels and somehow makes them more subtle. The scale of the piece is less intimidating – scarcely more than half the length of Vessels and broken into five movements instead of a single, relentless span. The surface resemblance to Feldman is closer, like his last orchestral works: Harrison takes up a musical element and, rather than develop it, gently turns it from side to side, like the facets of a crystal catching the light. Any listener lulled by this apparent familiarity may not even notice that they are slowly becoming disoriented. As each new movement begins, the mystery deepens. Have we heard this part before? Did the last movement change at all, really? Are we starting over from the same place, or will we end up where the last movement ended, only not to remember it when we arrive? Does each movement differ at all? Which movement are we up to? The musicians make the music float, as though without any physical reference for the listener to hold on to.

Linda Catlin Smith seemed to be a composer a little bit outside the usual sound-world of Another Timbre. What little I’d heard of her music up until now showed influences of folk music, particularly of traditions from North America. Based on that, I’d lazily pigeonholed her with the current generation of American composers who have found commercial success through exploiting a ‘vernacular’ of a steady pulse and conventional harmony. This was unfair of me. Dirt Road, a lengthy set of 15 movements for violin and percussion, was written 10 years ago but is making a wider impression only now.

Linda Catlin Smith seemed to be a composer a little bit outside the usual sound-world of Another Timbre. What little I’d heard of her music up until now showed influences of folk music, particularly of traditions from North America. Based on that, I’d lazily pigeonholed her with the current generation of American composers who have found commercial success through exploiting a ‘vernacular’ of a steady pulse and conventional harmony. This was unfair of me. Dirt Road, a lengthy set of 15 movements for violin and percussion, was written 10 years ago but is making a wider impression only now.

The title itself suggested an appeal to folksy authenticity that has been fashionable lately, in music as much as anywhere, and has already started to grate as much as the lumberjack shirt on an artisanal barista. Listening to the disc with that mindset becomes an astonishing revelation. The first movement is minimal, a violin drone supplemented with bass drum and occasional flourishes of vibraphone. The second suggests a folk influence, modal patterns to slow and brief to be considered full melodies. The pairing of instruments is peculiar, violin with percussionist, often on mallet instruments with occasional drum or cymbal. The first time I listened, the music went from pleasant, to strange, to captivating – it’s beautiful in a way that the listener can never settle into and take for granted.

Each new movement opens up a new perspective on the whole, returning to ideas heard before and presenting them in a new way, introducing a twist, opening up a new set of sounds that casts different light on what was heard before. Some movements can be quietly lyrical, others severely minimal, yet the work holds together as a unified experience, more than the sum of its parts. There’s a complexity of musical thinking going on here, belied by the simplicity of technique.

Violinist Mira Benjamin and percussionist Simon Limbrick play with a richly detailed grain to their sound, with edges just rough enough to give predominance to the physical sounds of the instruments that are so important to making the music work. Each moves effortlessly between foreground and background when needed. This CD has deservedly been getting a lot of attention. As Tim Rutherford-Johnson writes, “Smith’s time has, finally, come.”