I’m sitting in Cafe Oto thinking about why I’m too busy thinking to really pay attention to what Jon Rose and Chris Cutler are playing. I’m telling myself it’s good that I can listen without having to worry about paying close attention, and just let it fill the air around me, but I might need some convincing. I like the way there’s plenty of activity, both visually and aurally, but it’s all meshing together in a variegated carpet* of sound, not a pair of competing virtusosic showoffs – Barthes’ “petty digital scramble”*.

Nobody’s trying to impress me with how difficult it is to do whatever it is they’re doing, and even the most raucous sounds are giving room for me to think.

Filed under: Music by Ben.H

1 Comment »

The Slips

Sunday 11 April 2010

More details about The Slips can be found here. Audio excerpts and other documents will be available soon, once I’ve cleaned them up a bit.

Slips 1 and Slips 2 were written in March 1999 and revised in November 2002. They are two of several works I have written using musical compositional techniques to produce texts; in particular they are inspired by the formalist poetry of John Cage and Konrad Bayer. Unlike my previous texts (A Walk Around the Lake (1994-95) and An Austrian Automaton (1996- )) Slips 1 and 2 were written particularly with spoken performance in mind.

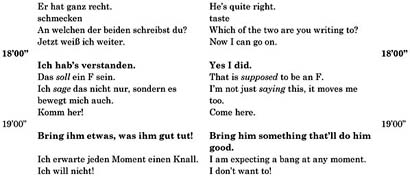

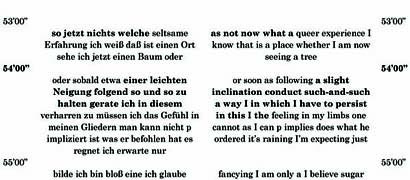

The matter for both pieces is taken from the slips of paper – Zettel – the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein kept in a box, in no particular order, which was discovered after his death. From this collection of short texts I have taken only the words and phrases written in quotation marks: examples of language, hypothetical speech, “things”, rather than the thoughts that connect or discuss them. A list of some 650 phrases or words was thus obtained.

Both works are one hour long, for two voices. For Slips 1, each minute was allocated a certain number of phrases, between zero and twelve, for each speaker to say. Apart from some specified timings, the speakers are permitted to say their phrases at any time within the designated durations. As well as speaking, the performers are instructed to write out specified passages while they say them. The number of phrases spoken, the selection of phrases from the list, the timings and designated written passages, were all determined by chance using Andrew Culver’s computer program ic, an I Ching simulator. With the exception of a small number of chance-selected phrases, the parts for the two voices in Slips 1 are almost identical, differing only in their timing and passages designated to be written out.

Slips 2 uses the same compositional method as Slips 1, but instead of complete phrases only a restricted number of words are selected from the given phrases. At first these words are extracted from the text for Slips 1, and after this material is exhausted newly-selected phrases from the list were subjected to this process. The parts for the two voices in Slips 2 do not differ at all, apart from their timings and designated written passages.

The two works may be performed separately, or with Slips 2 following Slips 1. Each work may be performed by two live speakers, or one live speaker with a recorded voice. As the text gives the original German and parallel English translation, each piece may be read out in either language, or a mixture of the two.

Two important aspects of The Slips in performance are the prevalence of silence (absence of consciously-produced sound) and the sense of time passing. One final point is the requirement for additional music to play very quietly sometime during the middle third of each piece. Other events may occur simultaneously with the performance.

The first complete performance of The Slips was given by myself at Clubs Project Inc. in April 2003. I performed both works twice, once reading each part, with a recording of myself reading the other part. The performance was entirely in English. To emphasise those two important aspects mentioned above, all the windows in the venue were left open throughout the afternoon of the performance, and the last of the four readings was times to conclude at sunset. During the second performance of Slips 2 the shadows lengthened across the room, and the candle on my table that I had lit at the start of the afternoon finally asserted its prominence as the only light source within the room.

At certain moments during the day, excerpts from my NSTNT HPSCHD PCKT MX (2002) for fourteen virtual, out-of-tune baroque harpsichords would play softly in another part of the venue, its presence more noticeable in its disappearances.

Other, smaller-scale pieces have been made from the same source material as The Slips. The most notable of these is Wandering Split (2002), an audio-only piece that was essentially a condensed version of Slips 1, spoken simultaneously in English and German, with a specially composed musical soundtrack acting as a third voice mediating between the two. Wandering Split was first presented as part of a sound installation in the group multimedia exhibition Gating, curated by Michael Graeve at West Space Art in 2002, and subsequently issued on the exhibition CD. Since then, the piece has enjoyed a few outings at sound art gigs in Austria.

Filed under: Art, Music, Writing by Ben.H

No Comments »

Please Mister Please XCV

Wednesday 7 April 2010

Ben Johnston, “Casta Bertram” (1969). Bertram Turetzky, contrabass; mix by Ben Johnston and Jaap Spek.

(10’46” 18.7 MB, mp3)

Filed under: Please Mister Please by Ben.H

No Comments »

Scrabble: Everything’s Officially Ruined Again.

Wednesday 7 April 2010

I wasn’t going to bother writing about the lame decision to change the rules of Scrabble to allow proper nouns. As half-arsed publicity stunts go, it’s only slightly more devestating than if the makers of Monopoly grandly announced they were rewriting their rules to allow players to quit when they get bored.

But now I’m thinking they’ve got a point. The makers of Scrabble have twigged that a fundamental aspect of the game has changed. This isn’t about giving Stoopid Kids These Days the edge – it won’t: you play Xzibit, I play Xerxes (and Xzibit).

The thing is that modern-day Scrabble is played by people who can access the OED on their smartphones, not to mention various online anagram tools. Letting in proper names brings back a lost fundamental of Scrabble: arguing. Arguing over who is or is not sufficiently famous to justify the latest mangling of “Brittany”. Convincing people there really is a Greek island called Aeaea. Debating which variant spellings of Mxyzptlk are canon. Like all authentic grassroots games, nothing is certain and it all ends in bickering, resentment and tears.

Filed under: Journalism by Ben.H

No Comments »

Hecker at Chisenhale

Monday 5 April 2010

Whether the effect were intentional or not, a single cough belied the purpose of this installation. Florian Hecker had four “sound pieces” installed at Chisenhale Gallery last month. That term “sound pieces” in the accompanying gallery text serves to remind everyone of the problem this type of show always brings up: that sound art is merely failed music.

In the gallery the show looked all very nice and professional, and did enough to fulfil the expected role of a sound art installation, yet not enough to succeed. There were four pieces, each of a specific length and played through a particular set of speakers. The gallery was thoughtful enough to provide a programme to give an idea of what you were getting and when, but this act had the side effect of raising the spectre of Ersatz Art: the special pleading for a piece of music or film displayed in a gallery to be judged on a different set of artistic criteria.

Should you sit (stand, actually) through the entire programme just to hear the first minute of the one you came in on, to say that you honestly “got” that whole piece? If you don’t like that long piece, should you be expected to wait through it to hear if the next one’s any better? These are probably not the questions the artist intended to raise with this show.

Three of the four pieces used directional speakers to create a spatialised distribution of sound through the large, resonant room. This seemed really cool until someone coughed or fidgeted and you realised that the room was so reverberant that any sound at all created the same effect. If that point was the work’s intention, then it was obscured by an apparent need to make composerly, musical gestures in each piece. This was especially the case with the fourth piece, which attempted to project contrasting movements of sound through the space, but was swallowed up by the room’s acoustics and ambiguous sonic material.

The most effective piece pointed a single speaker at a tiled section of wall at one end of the room, creating an impressive array of localised sounds from the echoes it generated. The other pieces lacked the clarity needed for the room.

The question remains, whether it is possible to present sound art purely as sound when its presentation, as here, is so dependent on the sense of time passing.

Filed under: Art, Music by Ben.H

No Comments »

A Toast to Thomas Angove

Thursday 1 April 2010

I’m breaking my impromptu holiday from blogging to pass on the sad news that Thomas Angove, inventor of the wine cask, has died at the age of 92. Not since the inventor of booze itself has one man advanced the science of getting an entire nation so drunk, so quickly, at so little expense. A large part of the art world will be forever in his debt.

Filed under: Art, Journalism by Ben.H

1 Comment »

Please Mister Please

Friday 19 March 2010

Big Star, “I Will Always Love You” (1975).

(3’42”, 5.08 MB, mp3)

Link fixed now.

Filed under: Please Mister Please by Ben.H

2 Comments »

A roundabout way of debating whether or not to pay £10 to see a performance of Monotone Symphony next week

Thursday 18 March 2010

Via greg.org, Google Street View of the street where Yves Klein “actually leapt into space one morning in 1960”. Fun fact I didn’t know: the famous photograph inspired Paul McCarthy to throw himself out of a window at art school.

“I hadn’t seen the photograph, so I jumped out feet first,” McCarthy says. “In the late ’60s when I see the image of him diving, I am shocked and I think, ‘Oh god, mine is so pathetic.’ And then, years later, it comes out that the photograph is a fake. That’s what’s so great.”

Once again, I’m back onto the ideas of radical amateurism and the desirability of distortion. I can’t find the references now, so I won’t mention the story of Nam June Paik being annoyed when Joseph Byrd performed Paik’s composition Playing Music (the piece which instructs the performer to make a 10cm cut in their forearm) because, as the instigator, he then felt obliged to perform the piece himself.

Instead, I’ll mention the time I visted the Louisiana Museum and saw a small group of little kids on the floor, clustered around one of the Yves Klein Anthropométries, painstakingly drawing copies, reproducting exactly each stray fleck of paint with coloured pencils and sheets of paper.

Filed under: Art, Music by Ben.H

1 Comment »

The Nostalgia File

Monday 15 March 2010

This was inevitable. I’ve been trying to find some of my old recordings to re-edit and pass off as new recordings for someone’s project. Of course, those recordings aren’t where I thought they were and now I can’t find them. Also of course, I’ve turned up a bunch of other old stuff instead, which I’d forgotten I had.

And so I’ve spent the evening listening to music with which I’m completely unfamiliar, even though I made it myself. It’s mostly stuff I obviously had no intention of using for “end product” at the time yet, compulsive hoarder that I am, set aside for possible future salvage. Usually this activity is about as optimistic as saving a small bowl of leftovers in the fridge, but in this case it turns out I may not have been quite as dumb as usual.

There is, as I hoped at the time, some stuff in here that interests me which I couldn’t hear when it was made, because I was too close to the process. At that stage of recording I was looking for a certain set of sounds, and I had to shut out everything that wasn’t relevant to my immediate goal – whether it was “interesting” or not – lest I get hopelessly lost amongst all these distracting details. I don’t need distractions; I can wander off-topic all by myself.

This experience has reinforced some ideas I’ve been clarifying in my mind for a while, about my relationship to my music. There should be some posts about these ideas soon, and some uploads of the salvaged tracks.

Filed under: Music by Ben.H

No Comments »

Please Mister Please

Sunday 7 March 2010

The Dixie Cups, Two-Way-Poc-A-Way” (1965).

(2’42”, 2.46 MB, mp3)

Filed under: Please Mister Please by Ben.H

No Comments »

Filler By Proxy LXXVIII: We connect August Strindberg with John Cage

Sunday 7 March 2010

Few outside of Sweden know that the playwright August Strindberg had periods of intense engagement with painting and photography in the 1890s, when his literary creativity had reached a deadlock. In an essay from 1894 called “Chance in Artistic Creation,” he describes the methods that he employs, speaking about his wish to “imitate […] nature’s way of creating.”* …

Strindberg distrusted camera lenses, since he considered them to give a distorted representation of reality. Over the years he built several simple lens-less cameras made from cigar boxes or similar containers with a cardboard front in which he had used a needle to prick a minute hole. But the celestographs were produced by an even more direct method using neither lens nor camera. The experiments involved quite simply placing his photographic plates on a window sill or perhaps directly on the ground (sometimes, he tells us, already lying in the developing bath) and letting them be exposed to the starry sky.

More about Strindberg’s Celestographs can be found at Cabinet, along with a translation of “On Chance in Artistic Creation“. (Found via greg.org.)

* A quote remarkably similar to John Cage’s “The function of Art is to imitate Nature in her manner of operation,” a thought to which he returned throughout his later life. Cage got this idea from reading Ananda Coomaraswamy’s The Transformation of Nature in Art. I don’t remember Cage making any references to Strindberg, and I don’t know how far east Strindberg extended his interest in exotic forms of spirituality.

* A quote remarkably similar to John Cage’s “The function of Art is to imitate Nature in her manner of operation,” a thought to which he returned throughout his later life. Cage got this idea from reading Ananda Coomaraswamy’s The Transformation of Nature in Art. I don’t remember Cage making any references to Strindberg, and I don’t know how far east Strindberg extended his interest in exotic forms of spirituality.

Filed under: Art, Filler By Proxy by Ben.H

No Comments »

Another gig – 24 February

Sunday 21 February 2010

I’ll be one of the performers of Dan Goren’s new group piece Sum Over Histories, as part of Music Orbit Showcase 3: 7.30pm on Wednesday 24 February 2010 at The Forge, 3–7 Delancey Street, Camden Town NW1 7NL. More info here – should be an interesting night of electroacoustic group improvisations and more. I’d tell you more but even I don’t know exactly what’s going to be happening.

Filed under: Music, Self-promotion by Ben.H

No Comments »

Please Mister Please

Thursday 18 February 2010

Josef Matthias Hauer, “Labyrinthischer Tanz, Op. III” (1953). Joseph Kubera and Julie Steinberg, piano.

(4’27”, 6.33 MB, mp3)

Filed under: Please Mister Please by Ben.H

No Comments »

What Was Music?

Thursday 18 February 2010

Filed under: Music by Ben.H

No Comments »

Rescreening: String Quartet No.2 (Canon in Beta)

Sunday 14 February 2010

When String Quartet No.2 (Canon in Beta) was exhibited as part of Redrawing in 2008, I added a video component to it, as a structural gesture to the work’s origins, and acknowledgement that it was being exhibited in a show of visual art. Fiona Macdonald kindly made me a video of a blank, white screen, which played on a continuous loop in the room while my cheap Malaysian laptop sat on a shelf and performed the music.

When I was asked to play the Quartet at the Vibe Bar last month I was also asked if I had a copy of the video to go with it. Even though I didn’t, I said yes, figuring that (a) it surely couldn’t be that hard to make a video of flat, solid white and (b) however bad it turned out it couldn’t be worse than having some random VJ doodling crap all over the wall behind you while you’re trying to play some music.

As it turned out, (b) the lovely people at Music Orbit don’t pull that gratuitous VJ shit, and (a) about as time consuming and frustrating as I thought it might be. There’s a video button on my little digital camera, which I’d never switched on before. I balanced the camera on a stool, pointed it at a flat white panel on a door, and let it roll.

You’d think there’d be nothing simpler, but it took a few goes and some playing around with the settings before I got something slightly acceptable. The gloomy English skies of January didn’t help much either, and I got 10 minutes of fairly solid grey. I played this back on my computer and made a handheld video of the screen. After too much time messing about with the movie editor software that came free with the laptop I got the final product, a soft grey that complements the muted monchromaticism of the music.

As the resulting video is a remake of a pre-existing work (originally made for an exhibition about remakes), and is itself a video of a video, the title Rescreening seemed apt. The 10-minute duration of the Vibe Bar performance makes it an ideal fit for YouTube, where you can play it to your heart’s content.